2014 Comic Book News Archives

June 21, 2014: Jack Kirby, Jimmy Olsen, and the Silver Age Superman

By T. Kyle King

By T. Kyle KingVirtually every fan of superhero comics is familiar with the Silver Age, and the vast majority of readers have strong opinions about that innovative and often wacky era. After the Comics Code Authority was established in 1954 to respond to Fredric Wertham's assault on the excesses of crime, horror, and romance comics, superheroes experienced a resurgence in print, beginning with the introduction of the new Flash in 1956 and blooming with the dawn of the Marvel Age in 1961.

Deserved praise for the Silver Age was offered by Brian Cronin, who recognized that, by limiting artistic options, the Code compelled creativity, much as budgetary restrictions demand cleverness from filmmakers. Cronin correctly credits comics creators for "the crazy inventiveness that went into these comics when it was necessary to give the superheroes busy work when they couldn't be shown fighting violent super criminals instead." Nowhere was that Silver Age sensibility more evident than in the pages of Superman's Pal, Jimmy Olsen.

The redheaded young reporter debuted, then flourished, in other media outside of comic books, initially appearing in the Adventures of Superman radio program in 1940 and attaining greater popularity when played by actor Jack Larson on the 1950s television show of the same name. The character's on-screen success prompted DC Comics to give Olsen his own title beginning in 1954, the year U.S. Senate subcommittee hearings on comic books and juvenile delinquency prompted publishers to create a self-policing content code. The series ran for 163 issues over almost 20 years.

Initially shackled by the need to follow the lead of the low-budget Superman television production, DC was able to unleash the creators of its comics involving the Man of Steel after the live-action series went off the air in 1958. Within the strictures of the Code, ingenuity and inspiration were given freer rein under the guiding hand of editor Mort Weisinger, and, as Glen Weldon approvingly observed, "writers and artists embraced what they were doing with an unself-conscious and profoundly imaginative glee."

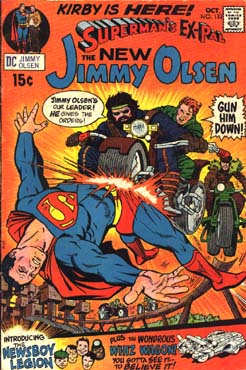

The Silver Age then began truly to come into its own for the Last Son of Krypton, with Jimmy Olsen being among the biggest beneficiaries of this blossoming. ComicsAlliance's Chris Sims stated the case plainly when he wrote: "In a lot of ways, Jimmy Olsen is the Silver Age, all of its excesses and strange rules and metaphors and inspirations brought together in a perfect snapshot of the time." Consequently, Sims dates the end of the Silver Age from the start of Jack Kirby's run as writer and penciller for Superman's Pal, Jimmy Olsen in October 1970.

The Silver Age then began truly to come into its own for the Last Son of Krypton, with Jimmy Olsen being among the biggest beneficiaries of this blossoming. ComicsAlliance's Chris Sims stated the case plainly when he wrote: "In a lot of ways, Jimmy Olsen is the Silver Age, all of its excesses and strange rules and metaphors and inspirations brought together in a perfect snapshot of the time." Consequently, Sims dates the end of the Silver Age from the start of Jack Kirby's run as writer and penciller for Superman's Pal, Jimmy Olsen in October 1970.

That demarcation, however, represents less an alteration of the destination than an adjustment to the direction by which it was approached. As Sims himself admits, the new author/artist's takeover of the title didn't mean the stories "were any less crazy - just that they were crazy in an entirely different way." Moreover, though Kirby used Jimmy Olsen as a vehicle for introducing new ideas by making Superman's Pal the starting point for the Fourth World saga, he began by reviving old ideas, bringing back the Newsboy Legion and the Guardian from the Star-Spangled Comics of the 1940s.

At the dawn of the Bronze Age, therefore, Kirby reworked familiar totems to make them weighty rather than whimsical, sublime instead of silly, and epic as well as absurd. The loopiness was retained yet imbued with a mythological dimension. For instance, Superman's 1968 comic book crossover with Jerry Lewis intrinsically is of a piece with Don Rickles's Jimmy Olsen cameo three years later, with the former depicting slapstick hijinks involving the blue suit and the latter playing for laughs the insult comedian's overreaction to otherworldly events.

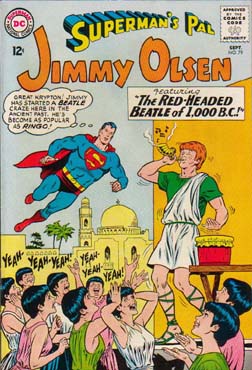

By the same token, it is not difficult to see the airy "balloon beasts" of the futuristic Action Comics #300 made more substantial, both literally and metaphorically, in the form of Transilvane, whereas Kirby's adolescent super-race of "Hairies" capped off with high-tech hippies DC's decade-long progression through '60s youth culture, which previously had seen the Man of Steel tangling with tough teens in 1962's Superman #151 and Jimmy Olsen famously bringing Beatlemania to Old Testament Judea in Superman's Pal #79.

By the same token, it is not difficult to see the airy "balloon beasts" of the futuristic Action Comics #300 made more substantial, both literally and metaphorically, in the form of Transilvane, whereas Kirby's adolescent super-race of "Hairies" capped off with high-tech hippies DC's decade-long progression through '60s youth culture, which previously had seen the Man of Steel tangling with tough teens in 1962's Superman #151 and Jimmy Olsen famously bringing Beatlemania to Old Testament Judea in Superman's Pal #79.

The cover of Kirby's fourth issue of Superman's Pal depicted a giant green Jimmy Olsen in a novel twist on the shopworn tradition of transformations by the redheaded reporter that previously had seen him turned into a giant green turtle man. Accordingly, the reader chuckles knowingly, but is not fooled, when, in that selfsame edition of his title, Jimmy tells Superman, "I'm just not ready to come face to face with campy bug-eyed monsters!"

Thus, in many respects, the Bronze Age was merely the continuation of the Silver Age by other means; had DC intended to authorize a wholesale overhaul, after all, the publisher wouldn't have commissioned Murphy Anderson and Al Plastino to re-draw Superman's face in Jimmy Olsen using the accepted house style. Unsurprisingly, the final issue of Kirby's brief run on Superman's Pal, Jimmy Olsen "proved to be a refreshing combination of both the old and new Olsen styles".

Kirby managed to bridge this gap between eras by bringing to superheroes a sensibility from other, more serious comic book genres. With collaborator Joe Simon, Kirby had created the romance comics concept and formed Mainline Publications, which produced the Western and war comics Bullseye and Foxhole, respectively. As Kirby confessed in his first issue of Superman's Pal, Jimmy Olsen, his background included stints generating My Date for teenagers, turning out Justice Traps the Guilty for crime readers, and "dabbl[ing] in witchcraft with Black Magic."

Perhaps most notably, the giant monster stories Kirby had been drawing for Tales of Suspense were imported into the superhero arena through 1961's Fantastic Four. Accustomed already to offering audiences more mature material in other comic genres, Kirby was able to add sophisticated layers underneath Silver Age superficiality, figuratively building new spires extending skyward by fortifying the existing foundations below the surface as he erected the Wild Area, Habitat, and the Zoomway in the vicinity of familiar Metropolis.

Nevertheless, Kirby was influenced by more than just his experience in different types of comic books, and there likewise was more to the Superman family bequeathed to Kirby in the aftermath of Weisinger's guidance than only obligatory oddness. In addition to the studied strangeness of stories by Otto Binder (who launched Jimmy Olsen's solo title), Weisinger's editorial oversight also provided "Brainiac, Bizarro, the full terror of kryptonite, [and] a gorgeous sprawl of Superman mythology" including the "survivor's guilt" that confirms author Larry Tye's observation that, "[w]hen a name ends in 'man,' the bearer is Jewish, a superhero or both."

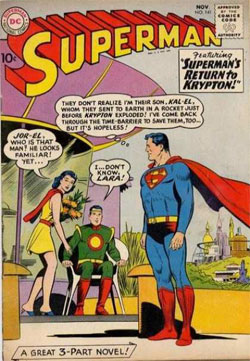

That Binder, Weisinger, and Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel, then recently returned to DC from the industry equivalent of exile, were ethnically Jewish is no coincidence; as noted by such observers as Danny Fingeroth and Rabbi Simcha Weinstein, the response of worldwide Jewry to postwar revelations about the extent of the Holocaust's horrors profoundly affected the Last Son of Krypton. Kal-El's status as the final survivor of his people formed the basis for such stories as Superman #141's "Superman's Return to Krypton" and the mythology-enriching and tragedy-deepening introduction of the bottle city of Kandor, confirming that the Silver Age already was delivering gravitas and pathos well before Kirby joined the DC masthead.

That Binder, Weisinger, and Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel, then recently returned to DC from the industry equivalent of exile, were ethnically Jewish is no coincidence; as noted by such observers as Danny Fingeroth and Rabbi Simcha Weinstein, the response of worldwide Jewry to postwar revelations about the extent of the Holocaust's horrors profoundly affected the Last Son of Krypton. Kal-El's status as the final survivor of his people formed the basis for such stories as Superman #141's "Superman's Return to Krypton" and the mythology-enriching and tragedy-deepening introduction of the bottle city of Kandor, confirming that the Silver Age already was delivering gravitas and pathos well before Kirby joined the DC masthead.

Kirby, too, was Jewish, though he had his name legally changed from Jacob Kurtzberg after using Anglicized pseudonyms from an early age. As importantly, he also was a World War II veteran, having drawn the dangerous duty of serving as an advance army scout sent ahead of his fellow soldiers to draw reconnaissance maps for use by the troops who came in behind him (many of whom read comic books as easily portable distractions while wearing olive drab overseas). This experience likely made much more of an impression on Kirby than did the military service of such fellow comic book professionals as Weisinger, whose wartime years were spent stateside writing scripts for army radio programs.

Hence, Kirby's background gave him the same cultural heritage on which Binder, Siegel, and Weisinger drew at their best, while his harder-edged experiences in uniform and in non-superhero genres enabled him to perform the delicate balancing act of staying true to the bigness and boldness of Silver Age ideas while deepening and enriching their symbolic significance. Maintaining that equilibrium was a daunting task, which since Kirby's day has seldom been sustained for any duration longer than the time it took for Grant Morrison's All-Star Superman to finish its publication run.

There are welcome signs, though, of a return to more suitably Silver Age-style storytelling. One of the defining conceits of the Silver Age, the so-called "imaginary story", has undergone a revival of sorts in such non-continuity books as the recent (albeit sadly short-lived) Adventures of Superman, which featured lighthearted tales in which Clark Kent served as a babysitter and Superman overheard two boys playing at being a superhero and a supervillain.

This departure from the confines of continuity allows artists the breathing room that produced the best work of the Silver Age, enabling creators to get superheroes and their supporting cast down to their essentials. Morrison expressly undertook this precise objective in All-Star Superman, and the best Adventures of Superman tales used this approach to turn offbeat stories into lessons about quintessence, as evidenced by Jeff Lemire's "Fortress" and Josh Elder's "Dear Superman".

For all the stylistic differences between the Silver, Bronze, and Modern Ages of Comic Books, then, the Superman family of titles retains a distinctive thread that runs throughout. Whether Jerry Siegel is sending Kal-El back to Krypton to deepen the sadness of the coming cataclysm, Jack Kirby is using Jimmy Olsen to launch a fundamental explication of the nature of good and evil, or Grant Morrison is revealing Superman's basic nature by examining the last days of the Man of Steel, the building blocks still stay the same, and there remains room enough for wild inventiveness to coexist with poignant profundity. By remembering the first principles of the Last Son of Krypton, comics creators can continue mining the most precious metals of every animated age.

T. Kyle King

2014 Comic News

Listed below are all the Comic News items archived for 2014.- January 2, 2014: Zatanna and John Constantine Join “Smallville” Comic Series

- January 6, 2014: Tom Taylor Looks Ahead at “Injustice: Year Two”

- January 8, 2014: Creative Team Discuss “The New 52: Futures End” Weekly Comic

- January 8, 2014: Superman-Inspired “God's End” Fan Comic

- January 9, 2014: Tony Bedard on Supergirl Becoming a Red Lantern

- January 12, 2014: Greg Pak Talks About the Batman/Superman Dynamic

- January 16, 2014: Supergirl to Join New “Justice League United”

- January 17, 2014: Lex Luthor to Join the Justice League

- January 30, 2014: Tony Bedard Explains Supergirl “Red Daughter of Krypton” Story

- February 4, 2014: Geoff Johns and John Romita Jr. are New “Superman” Creative Team

- February 5, 2014: Tom Taylor Talks Superman and “Earth 2”

- February 5, 2014: “Inside the NBA” Meets the Justice League

- February 7, 2014: Death of Superman in the New 52 Comics

- February 10, 2014: Scott Lobdell Leaving Superman After “Doomed” Saga

- February 10, 2014: “Robot Chicken DC Comics Special II” Variant Covers

- February 12, 2014: Klaus Janson on Inking “Superman” with Johns and Romita Jr.

- February 12, 2014: Download “The Justice League Goes Inside the NBA: All Star Edition” Comic

- February 13, 2014: Details on the “Superman: Doomed” Comic Book Crossover Event

- February 14, 2014: Johns and Romita Jr. Creating Something Big for Superman

- February 17, 2014: Neal Adams Talks “Arrival of the Supermen” 6-Issue Miniseries

- February 19, 2014: Tony Bedard Talks About Supergirl's “Secret Origin”

- February 23, 2014: Earliest Superman Cover Art Sold at Auction

- February 24, 2014: Josh Elder Talks About Emotional “Adventures of Superman” Story

- February 25, 2014: Superman Meets Power Girl in “First Contact” Comic Book Crossover

- February 27, 2014: 3D Motion Comic Book Covers Return in September

- March 1, 2014: Upcoming “Adventures of Superman” Schedule Announced

- March 3, 2014: Neal Adams Talks “Arrival of the Supermen” - Video Interview

- March 4, 2014: Steve Rude Reveals “Adventures of Superman” Cover Art

- March 4, 2014: DC Comics Unveils MAD Variant Covers for April Comic Books

- March 12, 2014: Golden Age to End Times Explored in Latest “Adventures of Superman” Story

- March 13, 2014: Charles Soule Redefining Superman/Wonder Woman

- March 13, 2014: First Look at “Superman #32” Cover

- March 14, 2014: DC Goes Retro with Bombshell Variant Covers for June

- March 18, 2014: Digital Comic Books - Poll Results

- March 24, 2014: The Inside Word on “Superman: Doomed”

- March 24, 2014: Shane Davis Video Interview

- March 31, 2014: Steve Niles Tells a Superman Ghost Story in “Adventures of Superman”

- March 31, 2014: Neal Adams Gives His Thoughts on the New 52 - Video Interview

- April 2, 2014: DC Cancels “Superman Unchained” #8-9 For Now

- April 3, 2014: Soule Talks “Superman/Wonder Woman” and “Superman: Doomed”

- April 7, 2014: Greg Pak Discusses “Action Comics”

- April 8, 2014: “Teen Titans” Set to Return in July

- April 9, 2014: Aaron Kuder Talks About the Future of Superboy

- April 10, 2014: Amazon Acquires Comixology

- April 14, 2014: Grant Morrison's “Multiversity” Set for August Release

- April 15, 2014: DC Comics Cancels “Adventures of Superman”

- April 21, 2013: Celebrating 76 Years Since “Action Comics #1”

- April 22, 2014: Superman: Doomed - Poll Results

- April 28, 2014: Superman Panel at C2E2 2014

- April 29, 2014: “Adventures of Superman” Cancellation - Poll Results

- May 7, 2014: Sneak Peek at “Superman #32” by Geoff Johns and John Romita Jr.

- May 7, 2014: “Adventures of Superman” - A Retrospective Examination

- May 12, 2014: USA Today Previews “Superman: Doomed”

- May 16, 2014: Greg Pak and Charles Soule Talk “Superman: Doomed”

- May 18, 2014: Motion Covers Return for September's “Futures End” Issues

- May 20, 2014: Johns and Romita Jr. Talk Up “Superman”

- May 20, 2014: Greg Pak's Focus on Superman's Supporting Cast

- May 22, 2014: Meeting Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster in 1939

- May 25, 2014: September's “Futures End” Superman Related Covers

- May 26, 2014: Golden Age and Silver Age Superman Origin Splash Pages

- May 27, 2014: “Superman: Doomed” Comic Book Story So Far - Poll Results

- May 28, 2014: Kuder on a Fresh Start and Farewell for Superboy

- June 1, 2014: Rare Copy of “Action Comics #1” Being Sold at Auction

- June 4, 2014: Greg Pak Talks About Infection in “Superman: Doomed”

- June 4, 2014: Rare Comic Book Collection Sells for $1.5 Million

- June 5, 2014: Joe Shuster Award Nominees Announced for 2014

- June 6, 2014: Bryan Q. Miller Brings “Chaos” to “Smallville” Comic Books

- June 12, 2014: Tony Daniel's Thoughts on Drawing “Superman/Wonder Woman”

- June 15, 2014: Exclusive Video Interview with Tom Taylor

- June 17, 2014: Exclusive Greg Pak Video Interview - Superman's Growth

- June 17, 2014: Exclusive Jerry Ordway Video Interview - Superman and Doomsday

- June 17, 2014: Exclusive Joe Kelly Video Interview - Superman and Killing

- June 18, 2014: John Romita Jr. Talks About Working on Superman

- June 21, 2014: Jack Kirby, Jimmy Olsen, and the Silver Age Superman

- June 23, 2014: John Romita Jr. Talks to USA Today About Superman

- June 24, 2014: Video - Sketching Superman's Power - John Romita Jr.

- June 25, 2014: Geoff Johns Talks About His Run on “Superman”

- June 26, 2014: Tom Taylor Looks at What's Ahead for “Earth 2”

- July 1, 2014: “Injustice: Gods Among Us” Year Three Announced

- July 1, 2014: Superman #32 - Poll Results

- July 4, 2014: Top Ten Super Superman Moments

- July 6, 2014: DC Comics Reveals Monster Variant Covers for October

- July 7, 2014: Neal Adams Questions Superman's Physical Appearance

- July 10, 2014: DC Comics Reveals “Selfie” Variant Covers for August

- July 15, 2014: Tony Bedard Taking Supergirl to “Futures End” and Beyond

- July 21, 2014: Tom Taylor Looks at the Future of Earth 2

- July 24, 2014: The Many (New) Faces of Superman

- July 24, 2014: Action Comics #1 Lands on eBay

- July 25, 2014: Superman and The Secret of The Machinist

- August 5, 2014: Injecting Optimism into “Superman” Comic Book

- August 6, 2014: Greg Pak Talks “Action Comics” - Video Interview

- August 7, 2014: LEGO Variant Covers for November Comics

- August 8, 2014: “Superman Earth One:�Vol 3” Cover Revealed

- August 8, 2014: Who is the Masked Superman in “Futures End”?

- August 10, 2014: More LEGO Variant Comic Book Covers Revealed

- August 10, 2014: A Look Back at “Superman #1” From 1939

- August 13, 2014: Supergirl Gets a Fresh Start in October

- August 13, 2014: Restored “Action Comics #1” Sells For $167,300

- August 14, 2014: John Romita Sr. Draws “Superman” Cover Debut

- August 14, 2014: Bidding on Finest Known Copy of “Action Comics #1” Starts Today!

- August 14, 2014: Greg Pak Explores Clark Kent's Humanity in “Superman: Doomed”

- August 16, 2014: Peter Tomasi is the New “Superman/Wonder Woman” Writer

- August 16, 2014: “Action Comics #1” Ebay Auction Hits $1.6 Million on First Day

- August 21, 2014: Frank Miller Says “I Love Superman”

- August 24, 2014: “Action Comics #1” Sells for $3.2 Million in Ebay Auction

- August 25, 2014: “Action Comics #1” Ebay Auction - Poll Results

- August 28, 2014: DC Comics Announces Jason Fabok as New “Justice League” Artist

- September 2, 2014: A Look Inside the Futures End Covers

- September 2, 2014: Worst Superman Comic Book Title - Poll Results

- September 3, 2014: Buyers of $3.2 Million “Action Comics #1” Revealed

- September 9, 2014: Darwyn Cooke Variant Covers for December Comic Books

- September 16, 2014: Superman Family Pivotal to DC Plans for 2015

- September 17, 2014: Tom Taylor Talks “Injustice: Year Three”

- September 18, 2014: Top 10 Classic Otto Binder Superman Creations

- September 18, 2014: Greg Pak Talks About “Batman/Superman: Futures End #1”

- September 23, 2014: Variant Cover Themes - Poll Results

- September 29, 2014: Long Beach Comic Con Panel Talks Lois Lane and Women in Comics

- September 30, 2014: Futures End - Poll Results

- October 2, 2014: When was Superman First Referred to as the “Man of Steel”?

- October 12, 2014: “Smallville: Season 11” Series Ends with “Continuity” Saga

- October 12, 2014: Comic Book News from New York Comic Con

- October 13, 2014: Bryan Q. Miller Officially Announces the End of “Smallville” Comic Book Series

- October 13, 2014: Straczynski Talks “Superman: Earth One - Volume Three”

- October 16, 2014: Scott Snyder Couldn't Be Prouder of “Superman Unchained”

- October 21, 2014: Team-Up Variant Covers for “Superman” Comic Books

- October 21, 2014: End of “Smallville: Season 11” - Poll Results

- October 22, 2014: Kate Perkins Talks About Writing Supergirl

- October 28, 2014: Read the $3.2 Million Edition of “Action Comics #1” Online

- October 29, 2014: Klaus Janson Talks About Inking “Superman” Comic Book

- October 31, 2014: Andy Diggle's Pitch for a “Superman/Judge Dredd” Crossover

- November 4, 2014: Scott Snyder Talks About the End of “Superman Unchained”

- November 4, 2014: Johnson & Perkins Send “Supergirl” to Intergalactic Hogwarts

- November 4, 2014: DC Comics Announces “Convergence” Crossover Event

- November 5, 2014: Behind-The-Scenes on the Conclusion of “Superman Unchained”

- November 6, 2014: DC Releases Full Image for “Convergence”

- November 11, 2014: Pre-New 52 Superman and Lois Return for “Convergence”

- November 12, 2014: K. Perkins Takes Supergirl to Crucible Academy - Video

- November 14, 2014: Harley Quinn Takes Over February Variant Covers

- November 18, 2014: New Titles Announced for Week Two of “Convergence”

- November 18, 2014: Fans Rate “Superman Unchained” - Poll Results

- November 18, 2014: Miller and Staggs Say Farewell to “Smallville”

- November 19, 2014: Johns and Fabok on “Justice League” and the “Amazo Virus”

- November 20, 2014: Dan Jurgens Looks Back on “The Death of Superman” 22 Years Later

- November 24, 2014: Shining a Spotlight on Gaslight Lex Luthor

- November 25, 2014: New Titles Announced for Week Three of “Convergence”

- November 25, 2014: Fan Interest in “Convergence” - Poll Results

- December 2, 2014: New Titles Announced for Week Four of “Convergence”

- December 3, 2014: Dan DiDio Discusses “Convergence”

- December 8, 2014: Greg Pak Gives Hints About Superman's Joker

- December 9, 2014: DC Comics Releases Details on “Convergence #0”

- December 11, 2014: Tom Taylor Out - Brian Buccellato In - “Injustice”

- December 11, 2014: “Superman #14” Available in Sunday's Comic Art Auction

- December 12, 2014: DC Comics Announces Movie Poster Variant Covers

- December 15, 2014: Tomasi on the Identity of Wonderstar in “Superman/Wonder Woman”

- December 15, 2014: Greg Pak Brings Horror to “Action Comics”

- December 16, 2014: Other Comic Books - Poll Results

- December 19, 2014: Would-Be Suicide Jumper Assassinated in “Batman/Superman”

Back to the News Archive Contents page.

Back to the Latest News page.