Superman Comic Books

Superman and the War Years

The Battle of Europe Within the Pages Of Superman Comics

Author: Wallace Harrington (wwh27539@mindspring.com)

I. Introduction

I. Introduction

Superman IV: The Quest For Peace is generally regarded as the weakest of the Superman films. However, it asked a question that most every Superman fan has asked at one point or another over the last 61 years: "If Superman is so powerful, why does he not simply put an end to all wars and suffering?" In many ways, the question implies a "God-like" quality for Superman that the publishers really don't want to address. It suggests that not only can Superman "change the course of mighty rivers and bend steel bars in his bare hands", but that he could actually change the course of human development and better their condition. It also implies that, if Superman had the choice that is what he would do.

Still, in Superman's history, the character has basically avoided interventions into the human follies of war in the comics focussing more on trying to affect the every day travails of simply surviving. Perhaps, even a Superman can see that humans have an amazing propensity for squabbling, and actually seek out reasons to go to war. It is far easier to deal with volcanoes erupting and tidal waves than dealing with wars and famine.

This wasn't the case in all of comics. Comic historians agree that the introduction of Superman in 1938, and his resulting popularity, launched not only a host of other characters, but also a whole industry. Many of the cast of early characters in Timely/Marvel's line were spawned directly from the war. Such creations of the 1940's as Captain America, The Human Torch, Sub-Mariner, and the All-Winners Squadron routinely battled the German and Japanese forces as part of the Allied front. With the nation focussed on war, it was surprising that many of DC's characters almost avoided stories of this nature which directly confronted the German and Japanese nations. The obvious exceptions to this were Wonder Woman, who was serving in the Army, and stories from All-Star Comics, where the Justice Society of America (Superman, Batman, Green Lantern, Wonder Woman, etc.) came together to battle for the American Way, and even visited with Franklin Roosevelt from time to time. However, in the long run, that may explain why many of DC's characters survived once the war ended while many of Timely's characters faded away.

II. Superman and The War Effort:

II. Superman and The War Effort:

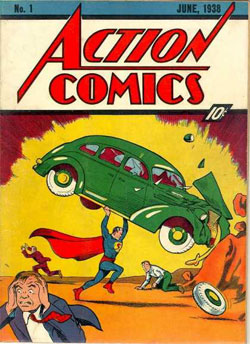

Superman burst onto the comic scene in 1938, and hit the ground running fighting oppression, bullies and petty dictators beginning with his first appearance in Action Comics #1. In that story, Superman traveled to Washington, DC, to confront lobbyist Emil Green and uncover corruption in the U.S. Senate. In his second appearance, in Action Comics #2, a more vengeful Superman matched wits with foreign spies, and Emil Norvell, a rich weapons magnate who tried to peddle influence in Washington, D.C regarding the war in the small South American country of San Monte. Superman was so upset with Norvell that not only did he send him packing from America, but he followed him to San Monte and even joined the San Monte army that, in 1939, greatly resembled Franco's Spain. In this story, in a bold and daring move, Superman kidnapped the leaders of both armies, took them to a field and told them to finish the war between themselves. Only after they realized that they had forgotten what they were fighting about did the war end.

As the war began to expand in Europe, and Hitler began his conquests of Belgium and France, there were numerous stories featuring foreign spies and cruel dictators, but they were careful not to specifically cite Germany or Italy as the subject country. Siegel was also careful not to name the dictator by any identifiable name (such as Hitler, or even Adolf), either. However, the characters he utilized were little more than thinly veiled parodies of the European dictators. In Superman #10 (May-June 1941), there was a story of the Dukalia-American Sports Festival. In that story, the Dukalian leader, Karl Wolff, gave a speech saying, "You have seen them perform physical feats, which no other human can. Proof, I tell you, that we Dukalians are superior to any other race or nation. Proof that we are entitled to be the masters of America." This was quite obviously inspired by Hitler's speeches prior to the 1936 Olympics held in Berlin, Germany where Hitler claimed that German athletes were superior to those of any other nation... Uber Mensch, or "Super-men". This was a claim quickly shattered by Jesse Owens.

Prior to 1941, Superman confronted several petty dictators from small countries that appeared to be in central Europe. In fact, until the US actually went to war with Japan, most of the stories in Superman comics that dealt with war used Europe as the backdrop. A notable exception was the story in Action Comics #30 (November 1940), where Superman fought Zolar, the bloodthirsty head of a band of Arab assassins, in the Sahara desert of Africa. There have been some discussions as to why that was. Many feel that because the publishers of several of the major publishing houses were Jewish, they produced comics which were very sympathetic to the European plight since they still had ties, and even relatives living in these countries.

IIa. The Covers of Superman and Action Comics:

IIa. The Covers of Superman and Action Comics:

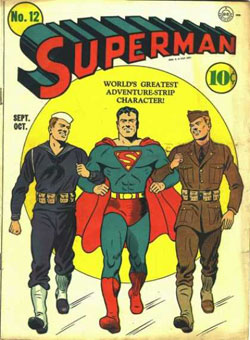

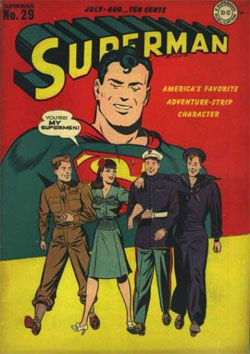

Obviously, the first thing anyone saw at a newsstand looking for a comic book was the cover. During the early years of comics, the covers did not necessarily have anything to do with any of the stories inside and were used more to attract a person's attention than to advertise the stories inside. Beginning with the cover of Superman #12 (Sept 1941) Superman began a solid propaganda alliance with American soldiers that continued through 1945 and the end of the war. That cover showed Superman walking arm in arm with a soldier and a sailor. From that moment on, Superman was shown sinking battle ships, tying cannon barrels into knots, and riding bombs toward "Japanazi's", a term first coined in Superman #18 (Sept-Oct 1942) to define the unified threat of Japan and German armies.

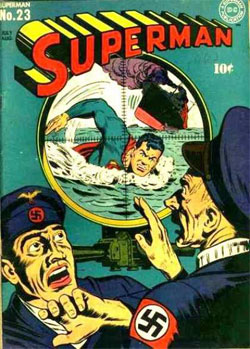

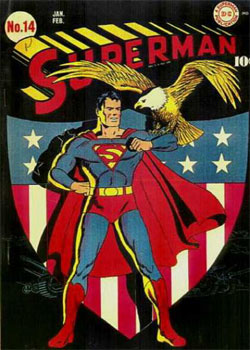

These covers were strong images and did serve the war effort as a sign of complete support. For example, Superman #23 shows Superman through a German U-boat's periscope swimming angrily toward the submarine after it had sunk a ship. There are also the several Jack Burley covers to Superman that have become famous for their very patriotic images. One of the best examples is the very patriotic image of Superman #14 (Jan-Feb 1941), showing Superman with an eagle on his arm before the American Shield. This cover was basically re-done for Superman #24 (Sept-Oct 1943) which showed Superman with a large American flag standing before what appears to be New York City. A modified image of Superman #12 was also re-used on Superman #29, which showed Lois arm-in-arm with an Army soldier, a Navy sailor and Marine and her telling them that, "You're my Supermen". The cover to Superman #34, was one of the last war-related covers. This cover appeared near the end of the war (May 1945) and featured a plea for help for the Red Cross.

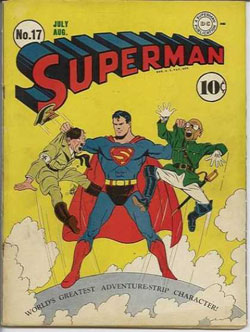

But, perhaps the most famous of these covers is the one from Superman #17 (July-Aug 1942). In that cover, Superman is shown standing on the Earth, holding both Hitler and the Japanese Emperor by the scruff of their necks and giving them a good shake as if that would put sense back into their heads.

Even more patriotic were the covers that appeared on Action Comics from 1941-5. Such wonderful Superman artists as Joe Shuster, Jack Burnley, Fred Ray and Wayne Boring routinely showed Superman attacking German and Japanese pill-boxes (Action Comics #31, #35, #39 and #53), destroying tanks (Action Comics #17, #40 and #59) or submarines (Action Comics #21, #54), and racing to protect American soldiers and sailors from imminent danger (Action Comics #10, #31, #48, #55, #60, #62 and #63). One of the most famous of these was the cover of Action Comics #60, drawn by Burnley, in which Superman delivered supplies and medicines to an American machine-gun squad fighting in the jungles.

IIb. Superman Stories:

IIb. Superman Stories:

DC needed a plausible plot device to allow Superman, and Clark Kent, to be outside of the draft and remain in Metropolis and not enter World War II, as most men were doing. In an interesting story, Clark Kent was drafted but failed his induction eye-exam, and was declared 4-F (undraftable) when he accidentally used his x-ray vision and read the eye chart in the next room. With this "error", Kent and Superman were free to work "from the outside" to affect the war.

Still, no matter how many patriotic covers appeared on the outside of Superman comics; it was actually rare that the action went further than the cover. By and large, the stories inside the comics remained morality plays and confrontations with villains like Luthor, The Prankster, Toyman and the Insect Master, not battles with the German army. Many stories mentioned the war in passing, but the actual number of stories that dealt directly with the war effort was rather small by comparison and initially dealt with petty dictators and terrorists. For example, in Superman #11 (July-August 1941), Superman battled Rolf Zimba, the head of the Gold Badge Organization, which was a group of terrorists determined to seize control of government beginning by blowing up a suburb of Metropolis.

So, while the covers were strong messages in support of the American troops, it may be that the stories inside intentionally avoided the subject of war as a means of escape for a weary nation. The country was constantly bombarded with news of the war, and the entire economic machinery of the US was focussed on building the war machine. So, stories of Superman battling Luthor were ways for soldiers and those at home to escape reality for a few minutes. However, because the nation was so focussed, it was impossible for DC to ignore it completely and for several issues there was at least one story which used the war as a backdrop.

Obviously, a common target for Pro-American stories during the war years was Hirohito and Hitler and both ended up as targets of Superman stories. In Superman #22 (May-June 1943), there was a story called "Meet the Squiffles", written by Jerry Siegel, which was actually a preliminary to Mr. Mxyzptlk (Superman #30, Sept 1944. "The Mysterious Mr. Mxyztplk" also by Jerry Siegel). This story was about an Imp from another dimension named Ixnayalpay (a Pig-Latin phrase for Nix-Pal or "No Friend") and his effect on Adolph Hitler.

America's Secret Weapon appeared in the next issue, Superman #23 (June-July 1943). In this story, Superman helped train troops by participating in war exercises and then congratulates the troops as being "Super-Soldiers".

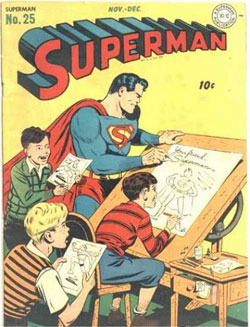

Superman #25 (Nov-Dec 1943) was unusual in that it featured two war-inspired stories that have come to be considered classics. The first, "King of the Comic Books" was a story about an arrogant comicbook creator and his character, Geezer. In the pages of Geezer Comics, Geezer fought the Nazi influence in Europe. In response, The German Bund, active in the US at the time, captured the comic artist because he portrayed the Feuher in an improper light. Superman, dressed as Geezer, arrived in the nick of time to save the artist and change his attitudes in the same panel.

Superman #25 (Nov-Dec 1943) was unusual in that it featured two war-inspired stories that have come to be considered classics. The first, "King of the Comic Books" was a story about an arrogant comicbook creator and his character, Geezer. In the pages of Geezer Comics, Geezer fought the Nazi influence in Europe. In response, The German Bund, active in the US at the time, captured the comic artist because he portrayed the Feuher in an improper light. Superman, dressed as Geezer, arrived in the nick of time to save the artist and change his attitudes in the same panel.

In the same issue is the wonderful story, "I Sustain the Wings", drawn by Jack Burnley. The story was written by Mort Weisinger directly for the US Military as a piece of war propaganda, and told the story of Clark Kent joining the Army Air Force Technical Training Command on assignment from the Daily Planet. This command was in charge of aerial reconnaissance, target optimization and general repair of bombers. This story helped explain to citizens exactly what this branch of the Army did, and bolstered support for its efforts.

Near the end of the war, Clark Kent was assigned to the U.S.S. Davey Jones, and served as a United States Navy war correspondent for the Daily Planet (Superman #34, May-June 1945).

One of the more famous wartime Superman stories actually appeared after the war ended thanks to the Department of Defense. "Battle of the Atoms" was originally going to appear in late 1944, but finally appeared in Superman #38 (January-February 1946) and featured a classic battle with Luthor save for the fact that Luthor's new weapon was an "Atomic Bomb". Since the Manhattan project, which gave rise to the first two American nuclear weapons, was in full swing in 1944, the Defense Department wanted nothing tipping off the Germans that America was even considering work on an atomic bomb, not even from a comic book. While the weapon used by Luthor looked nothing like the actual weapon, and was not anywhere near as destructive as the real bomb, government agents came to DC's offices and demanded that the story not be printed until official clearance was given, citing the need for a unified national defense. Obviously, the people at DC were confused, realizing that they must have come up with something more than their normal fantastic story.

Following that, another story, "Crime Paradise", was also censored and delayed. It ultimately appeared in 1946 in Action Comics #101 and told the story of Superman covering an atom bomb test, actually filming it for the Army. It featured a great cover by Wayne Boring and Stan Kaye showing an explosion with the now familiar "mushroom cloud".

IIc. The Superman Newspaper Strip:

IIc. The Superman Newspaper Strip:

As amazing as it sounds, during the later years of World War II, DC had several other instances where the Defense Department demanded that their stories not appear in print considering them a threat to national defense. In April, 1945, Alvin Schwartz wrote a story for the syndicated Superman newspaper strip, which involved the use of an atom smasher, or cyclotron. At the time, this concept was still science fiction, but Schwartz's story was close enough to reality that agents from the Defense Department demanded that the sequence not be run to eliminate the possibility of leaks. In an interview with Schwartz, he said, "I'd gotten my material about cyclotrons from a 1935 issue of Popular Mechanics, so I didn't have any idea about the bomb. I never even knew that the FBI got involved until years later when I saw an article in the New York Post which said, "Superman had it first," in other words, the bomb. The FBI had actually gone to Jerry Siegel who was in the armed forces at the time, but nobody mentioned it to me until years later."

Jack Schiff, an editor of the Superman comics and newspaper features, recalled in an interview that, "A pair of FBI agents visited DC Comics publisher Harry Donenfeld in early 1945. They insisted we get rid of the cyclotron, and bring the story to a quick conclusion. I refused to make the changes, so Donenfeld arranged for someone else to ghost the changes."

Once the war ended, there were several stories in Time and Newsweek mentioning the censorship of the Superman comic strips. In 1948, Harper's published a previously confidential memo written in 1945 by Lt. Col. John R. Lansdale, Jr, that outlined the War Department's discomfort with the information in these stories. The memo stated that they did not have enough staff to read all comic stories and proposed approaching the companies to police themselves. As Newsweek said, "while Superman could withstand a three-million volt bombardment from a cyclotron... what he couldn't take was the Office of Censorship, which asked McClure Newspaper Syndicate to discontinue references to atomic energy."

III. Other Print Media:

III. Other Print Media:

The February 27, 1940 edition of Look Magazine ran a two-page sequence written by Jerry Siegel and drawn by Joe Shuster entitled "What If Superman Ended the War?" In that sequence, Superman had tired of the destruction of war and decided to bring it to an abrupt end. He flew to Berlin and captured Adolph Hitler, then went to Moscow to capture Joseph Stalin. Leaping high above the mountaintops, Superman flew the pair to Geneva Switzerland, to a court before the League of Nations where the two dictators were placed on trial for war crimes against their own people. Interestingly, this was published before Roosevelt and Churchill invited Stalin to be one of the allies, and Russia joined in the battle against Germany. Still, it showed the sentiment toward Russia during the 1940's, and that even then the world opinion of 1940 considered the Russian people to be oppressed.

IV. Superman on Radio:

In 1940, Robert Maxwell, a writer who had been assigned the job of merchandising the Superman character, came up with the idea of transforming Superman from the comic pages to the airwaves. On Monday, 12 February, 1940, radio listeners first heard the words that have become indelibly linked to Superman as an American icon: "Faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive, able to leap tall buildings in a single bound. Look! Up in the sky! It's a bird! It's a plane! It's Superman!" Amazingly, it did not take long before the audiences of the radio show actually surpassed the number of people reading the comics.

Unfortunately, many of these radio broadcasts no longer exist in any form other than the written script. It was not a common thing to record the broadcasts, and tape recorders had not yet been invented. From the scripts that have survived, it is evident that World War II, and the events surrounding the war, served as the backdrop for several of the serialized stories. Again, one of the more famous episodes had to do with atomic energy and radiation.

In 1940, Jerry Siegel wrote a script for a story about a green meteor that arrives on earth from the planet Krypton. That story was never published. However, on the episode that aired on Thursday, 3 June, 1943, Clark Kent returned from an assignment, and discovered a green meteor in the desert. Mysteriously, it took his breath away and made him faint. Once Kent was rescued and recovered, he arranged to have the meteor taken to Dr. John Whistler, of the Metropolis Museum. Whistler identified the metal as coming from Krypton, and named it Kryptonite. Whistler had studied Krypton, and described to Superman, for the first time, what his planet had looked like.

Over two years later (September 21, 1945) a new storyline began which is widely regarded as the best of these serials (and is available on tape from the Smithsonian collection). The inspiration for this story was the use of the atomic bomb and the end of World War II. As the new story began, Clark Kent discovered that Dr. John Whistler had died and soon thereafter the Scarlet Widow, the most dangerous woman in the world, had stolen the Kryptonite. She enlists the aid of one of Superman's deadliest enemies, "Der Teufel" to kill Superman. Teufel (whose name means "The Devil" in German) is a Nazi spy bent on creating a super-soldier. Turning the Kryptonite to his own use, he used the meteor to transform German soldier Henry Miller into The Atom Man, with Kryptonite streaming through his veins. Miller plotted revenge for the defeat of Germany, and the destruction of Superman. This battle between Superman and the German Atom Man became a classic tale of Superman.

The Superman radio program continued on the air until 1951, and had a considerable audience. In fact, when Columbia made the decision to bring Superman to the movie screen in 1948, the credits read "Inspired by the Superman radio program broadcast on the Mutual Network," rather than referring to the comic books. This was understandable since the villain of the first serial, the Spider Woman, was definitely inspired by the Scarlet Widow sequences of the Atom Man radio series, and the story involved their search for Kryptonite to destroy Superman. The second of these serials appeared in 1950 and was titled "Atom Man vs. Superman", again inspired by the radio serial. However, this Atom Man was not a Nazi-super-soldier, but turned out to be Lex Luthor wearing a mask to hide his villainy as he sought to hold Metropolis in fear. (Both of these serials are available on video tape through Warner Brothers.)

V. Superman in the Cartoons:

V. Superman in the Cartoons:

If anything, it was the Superman of radio and movies that dealt more directly with war efforts and the threat of war than the comics. From 1941-1943, the Fleischer studios produced a wonderful series of cartoons featuring the Man of Steel. These cartoons are striking for their wonderful artwork and animation, and their stories remain truthful to the Superman character. Four of these cartoons dealt directly with the war effort. Japoteurs (Episode #10, Released: September 18, 1942) is a blatant war-time cartoon featuring Japanese spies as the protagonist and, thus, serve as direct propaganda against the Japanese. On the inaugural flight of the world's largest bomber, Japanese agents steal the plane, and use it to bomb the airfield preventing pursuit planes from taking off. Seeing the disaster, Superman soars up to the plane and finds that Lois Lane has been seized as a hostage for leverage to force Superman to leave the plane. Eventually, Superman saves Lois, and returns to capture the Japanese spies, only the controls have been destroyed and the plane loses altitude. Realizing that he can't fix the situation from inside the plane, Superman grabs Lois. He puts her on the ground, and flies back to slow the descent of the bomber and manages to avoid a crash.

Another overt war cartoon is The Eleventh Hour (Episode #12, Released: November 20, 1942). This cartoon begins with Lois and Clark sent to Yokohama, Japan to investigate reports of sabotage. As the clock strikes eleven, we see a ship being taken from the yard and sunk. Searchlights fill the sky and Superman leaps from his hiding place behind a girder and returns to his room where he quickly changes into Clark Kent. Lois, hearing all the noise, asks Clark what is going on. "Sabotage... I hope." "Me, too," Lois responds. Japanese troops go on the alert and when the clock strikes eleven the next night, Clark changes into Superman, pulls the iron bars away from the window of his room, and flies out to sea where he sinks a tanker. Realizing that Lois Lane is a connection to Superman, Japanese soldiers arrest her and threaten to kill her unless Superman surrenders. Superman has been at sea destroying another ship and returns just as the signal to shoot Lois is given. Swooping in front of Lois, Superman deflects the bullets and lifts Lois away to safety and home. With Lois safe in Metropolis, the film ends with a clock tower in Yokohama striking 11 and Superman continuing his reign of terror.

While those two episodes dealt with the war in Japan, Jungle Drums (Episode #15, Released: March 26, 1943) dealt with Lois and Clark discovering that Nazi forces were using an African temple as a base and were deceiving natives by making them think the Germans were priests. Lois Lane's plane was shot down on the way to rendezvous with an American convoy. Later, as Clark flies over the area on the way to the same rendezvous. Kent sees sacrificial fires and the wreckage of a plane, parachutes down, changes into Superman and rescues Lois. The natives are shocked to see him come out of the fire with her in his arms, and jungle drums stop. The Nazis strike back at Superman and during the battle Lois puts on one of the natives' costumes and enters the base in hopes of warning the convoy. The Nazis capture her, and Superman springs to her rescue. Lois warns the U.S. forces in time to save the convoy and cause an entire fleet of Axis submarines to be destroyed.

The very last of these Superman cartoons was Secret Agent (Episode #17, Released: July 30, 1943) and began with Clark Kent on a phone in a drugstore arguing about his assignment when he sees cars crash in front of the store and shooting erupts. Dropping the phone, he chases the cars and sees a woman emerge from one of the cars carrying a briefcase. Suddenly, the band of saboteurs who were chasing the woman captures Clark, and they lock him in a closet. The woman races to the police and tells them that she has been pretending to be part of the saboteur group for the past six months to put together a list of names and their plans which she must get to Washington. The police give her an escort to the airport, but on the way to the airport the woman's escort is shot. Grabbing the wheel, she drives on toward an ambush the saboteurs have planned at a drawbridge. Leaping from the car, she tries to lower the bridge but falls into the bridge gears. Clark "wakes up" changes into Superman, and flies to the bridge where he saves the agent in the nick of time and flies her to Washington D.C. In a very patriotic climax, the cartoon ends with her revealing the insidious plans of the saboteurs and the flag waving in the background.

V. Conclusion: Was Superman a force in World War II?

During the years that encompassed World War II, everyone in the US pitched into war effort in some form or fashion. Children raised money for War Bonds. Women took over factory jobs to replace the men that had left for war. Even comic book characters took up the fight. From Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, to Popeye, from Captain America and Bucky to Batman and Robin and Superman the comic characters did their best for the GIs. But, obviously they couldn't fight the war, or turn the tide. What they could do was help elevate the morale of the soldiers actually on the fronts.

DC Comics, for the most part, kept the wartime stories featuring their characters on a more personal level. The stories involving the majority of their characters were not epic battles of good versus evil (read Allies vs. Axis) but were more about them helping soldiers, catching spies, or delivering supplies to the front to assist the war effort, but not take it over. Very rarely would they show their more powerful characters, (Superman, Green Lantern, Starman, Wonder Woman or the Flash) actually destroying the weapons of the Axis powers in force to bring a lasting peace. The sad truth is that you could only do that once and each of these characters had a monthly comic to fill. And, in fact, the war raged on with many battles with nary a superhero in sight. So, to keep some sense of reality in that comic book fantasy world, DC's character made the little contributions rather than the large final one.

Still, I'm sure that on some warm summer night in 1941, there must have been a couple of kids sitting on a hill overlooking a small town in Kansas who stared at the stars and dreamed, "If Superman were real he'd show those Nazis what for." They would have dreamed, like every other kid who tucked a bath towel into their t-shirts and pretended to fly around the room, that Superman WAS real. And that if he somehow appeared and stood before them, right then, he would most definitely do the right thing because he was Superman. For he could "change the course of mighty rivers and bend steel bars in his bare hands", and then, as now, Superman was the symbol of truth, justice and the American way.