Interviews

Exclusive Interview with Elliot S! Maggin

[Date: January 2009]

Superman Homepage Exclusive Interview with Superman Writer Elliot S! Maggin

Superman Homepage Exclusive Interview with Superman Writer Elliot S! Maggin

Elliot S! Maggin began writing for Superman with 1972's instant classic "Must There Be a Superman?" in Superman #247 (1st vol.). He remained one of the principal writers of the comic book adventures of Superman through 1986 when the Silver Age Earth-1 Superman retired happily in Alan Moore's "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?" finale.

Early on at DC, Maggin received the exclamation point in his middle initial that would follow him the rest of his life. It was a happy accident that resulted from a typing error. Maggin used exclamation points in scripting as periods often disappeared in the printing process. While typing his own name, he accidentally struck the exclamation point where the period following his middle "S" initial would have gone. Since then, he's been known to comic book fans as Elliot S! Maggin.

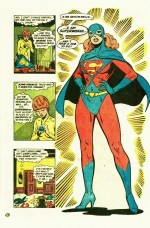

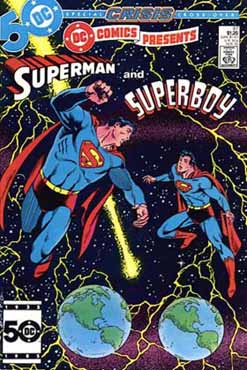

Maggin is credited with creating Superboy-Prime, who first appeared in Maggin's DC Comics Presents #87 story "Year of the Comet" before Prime moved onto his role in "Crisis on Infinite Earths" (where he remained in limbo until "Infinite Crisis"). Maggin also created Superwoman in DC Comics Presents Annual #2 story "The Last Secret Identity". A similarly attired Superwoman is currently making a return to Superman continuity in the Sterling Gates-penned Supergirl title.

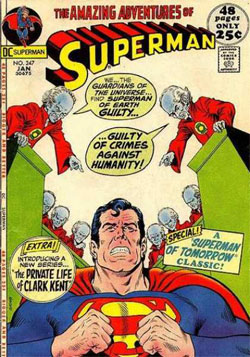

In addition to authoring Superman's comic adventures, Maggin wrote two original Superman novels published in conjunction with 1978's "Superman: The Movie" and 1980's "Superman II". The first novel, "Superman: Last Son of Krypton", places the characters firmly in Earth-1 continuity of the time, with Clark Kent co-anchoring the WGBS News with his old Smallville gal pal, Lana Lang. The novel recaps Superman's origin story - including his tenure as Superboy - and puts an unexpected twist on who Jor-El had intended to find the baby Kal-El's rocket. The core relationship of the book, though, is the long-standing friendship turned super-villain sour that existed between Superboy/Superman and Lex Luthor.

As "Superman II" revved up the level of villainy to include the devilish General Zod, Maggin's second novel "Superman: Miracle Monday" does likewise - times a zillion. Maggin reaches much lower than Zod in his choice of villain - C.W. Saturn, a.k.a. the Devil himself.

In "Miracle Monday", Maggin borrows a character concept from a comic book story "The Miracle of Thirsty Thursday" in creating time traveler Kristin Wells. Wells journeys back in time to figure out the mystery of the origin of Miracle Monday, a holiday celebrated for centuries on the third Monday in May - though nobody has any idea why.

In "Miracle Monday", Maggin borrows a character concept from a comic book story "The Miracle of Thirsty Thursday" in creating time traveler Kristin Wells. Wells journeys back in time to figure out the mystery of the origin of Miracle Monday, a holiday celebrated for centuries on the third Monday in May - though nobody has any idea why.

Kristin Wells the observer becomes Kristin Wells the story when she's possessed by Saturn and exposes Clark Kent as Superman live on the 6 PM Metropolis News. Saturn is determined to morally denigrate the Man of Steel in every way and, of course, Lex Luthor plays an important role again - though not necessarily as the villain of the piece. Superman is given a choice between saving one life - that of Kristin Wells - and saving billions. Rather than let any one die, Superman saves Kristin and the rest of the planet, and manages to find a way to bring Clark Kent back from the dead too. Though nobody in Metropolis remembers, Superman literally saved Metropolis and the world from Hell itself - the good feelings that remained after Superman's ultimate victory became the basis for the very first Miracle Monday.

Kristin Wells becomes a comic book character herself a few years later when she's introduced as Superwoman in the aforementioned DC Comics Presents Annual #2. The Annual places "Miracle Monday" firmly in pre-Crisis comic book continuity. Once again, Kristin time travels to observe and ends up becoming the story. Graduating from student to teacher, Wells time travels to Metropolis to find out the last unknown secret identity, that of Superwoman. Kristin believes it could be Lois or Lana or even Supergirl. But she's shocked by the only possible answer - that she is Superwoman and her powers derive from her future technology.

Maggin ceased writing Superman for DC with the "Man of Steel" reboot. However, Maggin has written several stories published on the internet dealing with the Superman family, including a Krypto the Super Dog story titled "Starwinds Howl". Since leaving the comic book industry, Maggin, always active in the Democratic Party, became interested in running for political office, which he attempted in Congressional bids in 1984 and 2008.

In 1998, Warner published a Maggin-authored novelization of the Mark Waid/Alex Ross mega-smash "Kingdom Come". The book returned Maggin to his former job of putting words in Superman's mouth in an official (i.e., licensed) capacity for the first time in more than a decade.

The Superman Homepage would like to thank Mr. Maggin for taking the time out of his schedule for this interview.

Q: Where were you born and raised? How old were you when you began writing for DC?

A: I was born in Brooklyn and I grew up on Long Island. I was a student at Brandeis University near Boston when I wrote the Green Arrow story that was eventually my first sale to DC. I was 19, I think, when I started writing it and 20 when Julie Schwartz sent me a letter offering to buy it.

Q: Just prior to you joining DC as a writer, Elliot Maggin the fan had a letter to the editor printed in the back of 1971's Superman #238. Your letter compared Superman to literary legends, referred to comics as mythology, and psychoanalyzed Superman's motivations. Did you have a sense that you were seeing subtext, allegory, and mythology where few others had taken the time to see it before?

A: I did see that in the character, pretty much always had, but I don't think I was the only one. I had written a paper for a humanities class comparing Superman to Achilles, talking about the classical themes that recur in the literature of archetypal characters. I think there's something hard-wired in the human brain that causes us to suck up stories of that sort and make them a permanent part of our consciousness. They're not a product of the cultures in which they arise, but rather a defining aspect of a culture's character. I'm always talking about what America is becoming, insisting that the American Revolution wasn't an event but a long-term trend and people who don't identify strongly with heroic fiction generally don't understand what I'm getting at. I think that the nature of Superman, the orphaned immigrant who rights wrongs and leads by example, is a significant indicator that bodes well for what our culture is evolving into.

Q: How did your first assignment for DC Comics - a Green Arrow story - evolve out of a college project?

A: I was taking a class on Twentieth Century American history and I was part of a section of that class, led by a graduate student, concentrating on the development of media. I had read about comic books being distributed in South America by government agencies, instructing people on how to do certain things and spreading information - presumably with a pro-government slant. I wanted to illustrate in my paper for this class that even in an industrialized country like ours comics were a viable tool for spreading political information. So the bulk of my paper was a script for a 19-page Green Arrow story in which the hero decides that his next logical step in having a positive impact on his community was to run for public office. I got a B-plus and thought I deserved better, so I sent the script to Carmine Infantino, who was president of the company - it was called National Periodicals Publications - at the time.

Q: How did your relationship with Julie Schwartz begin? What did that relationship evolve into professionally and personally over the years under his editorship?

A: I got to meet Julie because Carmine passed along my script to him. He didn't have time to read it but apparently both he and Carmine were impressed enough with the letter I sent with it that they didn't just toss it. Julie handed it off to Neal Adams, who read the script and liked it, and told Julie it was worth buying. Julie read it, asked me to shorten it to 13 pages, then he bought it and Neal drew it.

Julie was just 55 when I met him, which is younger than I am now. I thought he was unspeakably old. He looked about 60, I thought. He always looked about 60, even when he was in his 80's. We got very close over the years. I guess we either had similar temperaments or I learned at an early age how to be a cranky old fart from him. Julie was someone I really loved. He's one of the mentor figures, one of the really important people of my life.

Q: What do you recall about your first Superman story in Superman #247? Did Julie Schwartz approach you to write a Superman story or did you pitch him? How is it that a teenaged Jeph Loeb apparently factored into the development of that first story?

Q: What do you recall about your first Superman story in Superman #247? Did Julie Schwartz approach you to write a Superman story or did you pitch him? How is it that a teenaged Jeph Loeb apparently factored into the development of that first story?

A: Julie just said, when I came to deliver my Green Arrow story, something like, "Want to take a crack at a Superman story?" I told him sure, and I went back to Boston and spent about two weeks thinking about what I could bring to him. Denny O'Neil had just left off doing his big Super-Sandman series, which was the first attempt Julie made at imprinting his editorial style on the character. Denny just didn't want to do any more Superman stories. So I decided to come up with eight or a dozen sketchy ideas to throw at Julie when I came back to town. In the interim, I had dinner at the home of Dave Squire, who was Jeph Loeb's stepfather and the vice president of the university where I was a junior at the time. Squire was another of my mentor figures. I had two of them at Brandeis, and now one of them in New York. I had met Jeph before. He was about 12, and he seemed to be one of those Marvel-is-great-and-DC-sucks kind of fanboys. I spent most of the time I spent with his family, I think, arguing with Jeph over whatever. I remember he wanted me to create a teenage sidekick for Superman and I thought that was an awful idea. Probably would have named him Jeph, though. I can't for the life of me remember the conversation where he suggested a Superman story where the hero decides he's being too heroic for humanity's good, but he wrote it down and gave it a title: "Why Must There Be a Superman?" So a few days later, when I went to see Julie with ten or so sketchy ideas scribbled on a legal pad, this sociology treatise that turned into Superman #247 was the idea that Julie latched onto. So we worked it all out, with the Guardians planting an idea in Supes' head and making him have second thoughts about solving the problems of a bunch of Mexican farm workers in California. I didn't realize I'd tossed out Jeph's idea until he told me 20 years later. There was a little orphan kid in the story who helped Superman figure out what to do, and at the time I probably thought it was Jeph, but in retrospect I think it was probably César Chavez.

Q: During your run on Superman, the character and stories seemed to start growing up and comics generally began to appeal to older readers - was this a conscious choice on the part of you, Julie, and the other writers?

A: I think I was growing up, is the real reason. I used to say I was writing stories that I'd enjoy myself and Julie thought that was just awful. He thought I was much too old in my twenties to be enjoying the kinds of stuff he was looking for. He didn't realize I was stuck in emotional pre-adolescence - which was ironic for a teenaged grandfather like him.

Q: How often did you work with Cary Bates? What was the writing process like with a co-writer vis a vis a solo project?

A: I worked with Cary every chance I got. We probably collaborated on three series of stories that I can remember offhand. It was a lot of fun to work with him. I've never since been able to figure out how to divide the labor so effectively between myself and a collaborator. He would write the scene descriptions and I'd write the dialog and both of us thought the other was doing most of the work. I wrote dialog like I'm talking out loud - in fact I often do - and Cary has a very visual sense of a story's progression. Usually a collaboration involves twice the work for half the money. This one really worked.

Q: How on Earth-Prime did you and Cary come up with the idea to write yourselves into Justice League of America #123 and 124? How did you decide Cary would be the bad guy and you the good guy? Do you really have the personality of Green Arrow, as your 'character' said in JLA #123?

A: You remember a Batman story called "Night of the Reaper"? It was about an adventure Batman had in Rutland, Vermont at Tom Fagin's Halloween party. Tom was a real guy who had a real comic book Halloween party every year, and Neal and Denny did this story around that party and wrote and drew in some of the people who were at the party the year before I met them all. Alan Weiss was the victim of this Batman villain. It was a great story, but it kicked off a long sloppy string of bad stories incorporating their writers and artists as characters. Cary and I both hated it when guys we knew would turn up as comic book characters, so we decided that the way to stop the trend was to involve ourselves in a story so impossibly self-serving and ridiculous that no one would ever do it again. So we did that Justice League/Justice Society crossover where Cary was the villain and I was the hero - I think we tossed a coin. We wrote the entire script for part two in under two-and-a-half hours. I did speak like I had Green Arrow talking in those days. Very salty and colorful. I'm a colorful guy. Turned out this awful story was a huge hit. I got hot fan mail and stalkers in the deal. So what it kicked off was an epidemic of writers and artists popping up in their own stories in the hope of scoring. I guess it was good and bad in that way.

Q: You've worked with legendary comic book artists including Curt Swan, Murphy Anderson, Carmine Infantino, Dick Dillin, and Alex Toth, to name a few. You and Cary Bates are both closely associated with Curt Swan but do you have a personal favorite?

A: Those guys are all terrific. Curt was another cranky guy I eventually got very friendly with. Dick Dillin was like this walking, breathing Captain Kangaroo. Probably my favorite artist though just in technical terms - and I never really did get to know him - was Alex Toth. I think everyone should draw just like Alex Toth. He was like Rembrandt at middle-age. He could take a chunk of charcoal and smear it over a page in one swipe and there'd be eyelashes there. I don't know what kind of foofaraw you have to go through to grow talent like that, but I'm in awe. Ask any illustrator you know; he'll say the same thing.

Q: Who decided that, rather than write script adaptations of "Superman: The Movie" and "Superman II", you would write original novels set firmly in Earth-1 comic book continuity?

A: Nobody really decided it, but Mario Puzo made it necessary. I had written a film treatment for a Superman movie in 1974 and made a case to Carmine about how the time of heroes was returning and it was getting to be time for a Superman feature film. He seemed to agree, but rather than think about my treatment he must have made the same case to the guys at Warner Bros. A year or so later Alfie Bester showed up at the office and wanted to talk to me about a Superman movie he was negotiating to write. That fell through, and not long afterward I came in one day and there's Mario Puzo wanting to have the same conversation Bester had been interested in. Cary and I spent two days in a conference room with Mario explaining how Superman was basically a Greek tragedy (those were Mario's words, actually) and then he went off to write his movie. So I dusted off my film treatment and went upstairs to Warner Books and asked them to consider my story for a novel. That was Last Son of Krypton. It was never supposed to be a movie tie-in. It was supposed to be released midway between the first two films to keep the franchise afloat in the interim. Mario had the rights to do a novel adaptation of his film, but he got all tripped up in Hollywood politics and wasn't able to do it. He sat on the rights, though, so no one else could do it, and they put my book out the same day the movie was released. There were nine publishing products that came out with that movie and mine was apparently the only one that sold worth a damn. Neal had done a comic booky cover for the book. Beautiful stuff. But they substituted a movie still and the next time I saw Neal's cover it was in around 1989 in an Andy Warhol swipe at the Museum of Modern Art. Warhol claimed it was "adapted" from a Superman drawing circa 1955 or so - but it was clearly Neal's Superman novel cover from 1978. I don't know whether Neal ever saw that Warhol exhibit - he used to go to the Museum a lot - but I doubt he ever tripped over Warhol's swipe of him. I should tell him about it.

Q: In your first Superman novel, "Superman: Last Son of Krypton", Albert Einstein plays a pivotal role. You also wrote Einstein as Lex Luthor's personal hero in the comic books. What does Einstein mean to you?

Q: In your first Superman novel, "Superman: Last Son of Krypton", Albert Einstein plays a pivotal role. You also wrote Einstein as Lex Luthor's personal hero in the comic books. What does Einstein mean to you?

A: Einstein is one of my childhood heroes - like Superman and John Kennedy. I used to do book reports on him in grade school. When I was 12 I used to tell people I wanted to be a theoretical physicist when I grew up. There was a Shadow story I wrote at one time that took place in Princeton about a famous Jewish scientist's escape from Nazi Germany. My mom lived just four or five miles from Princeton, growing up. There was a final scene in that story of a girl named Sally Herman - my mom's childhood name - selling him an ice cream cone in the ice cream parlor on Nassau Street in Princeton. That really happened to Einstein the day he landed in New Jersey - except that it wasn't actually my mom behind the counter. I still read abstruse volumes on physics for fun, and one of my two favorite books of the past year is Walter Isaacson's biography of Einstein. He's a big deal for me.

Q: During your tenure on Superman, you created Superwoman for a "DC Comics Presents Annual". Superwoman was secretly - even to her at first - Kristin Wells, a time traveler who first played a pivotal role in your second Superman novel, "Superman: Miracle Monday". You've said before Kristin is based on a character from Superman #293 story "The Miracle of Thirsty Thursday". How did the Kristin Wells character evolve from "Thirsty Thursday" to "Miracle Monday" to Superwoman?

A: When I wrote "Thirsty Thursday" the time-traveling girl in it was Joanne Jaime, who looked a lot like my girlfriend Joanne at the time. I thought the best gag in that story was about crowds of time travelers gathering around historic events so that all the hotels filled up and you couldn't get a cab. Sort of like Washington when President Obama gave his inaugural address. I once tried to sell a story to the National Lampoon called "The Plot to Save Lincoln" where this guy went back in time to foil the assassination and found the audience in Ford's Theater full of people from different time periods tripping over each other to do the same thing. That was the germ of the idea for Miracle Monday, where Kristin Wells - who was actually the five-year-old daughter of a subsequent girlfriend; I was busy in those days - traveled back in time from the 27th century or so to research a doctoral thesis.

A: When I wrote "Thirsty Thursday" the time-traveling girl in it was Joanne Jaime, who looked a lot like my girlfriend Joanne at the time. I thought the best gag in that story was about crowds of time travelers gathering around historic events so that all the hotels filled up and you couldn't get a cab. Sort of like Washington when President Obama gave his inaugural address. I once tried to sell a story to the National Lampoon called "The Plot to Save Lincoln" where this guy went back in time to foil the assassination and found the audience in Ford's Theater full of people from different time periods tripping over each other to do the same thing. That was the germ of the idea for Miracle Monday, where Kristin Wells - who was actually the five-year-old daughter of a subsequent girlfriend; I was busy in those days - traveled back in time from the 27th century or so to research a doctoral thesis.

Q: Prior to the "Crisis on Infinite Earths", which re-established Superman as the only guy in town with an "S" on his chest, Superwoman had only appeared briefly, though one of those was a cameo in Alan Moore's "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?". Did Superwoman get a fair shake? How do you feel about the recent return of a similarly garbed mystery Superwoman to Superman continuity?

A: I'm not sure. But I've gotten to be a serious Alicia Keys fan, if that's at all relevant.

Q: You also created Superboy-Prime in DC Comics Presents #87. Did you know at the time you created the character what fate and Marv Wolfman had in store for him at the end of "Crisis"? It seemed he had been created so a Superboy could actually be seen going away - as if it were as a symbolic gesture that the Superman as a superkid concept was going into retirement. Was that the case?

Q: You also created Superboy-Prime in DC Comics Presents #87. Did you know at the time you created the character what fate and Marv Wolfman had in store for him at the end of "Crisis"? It seemed he had been created so a Superboy could actually be seen going away - as if it were as a symbolic gesture that the Superman as a superkid concept was going into retirement. Was that the case?

A: Creating characters is like having kids. You teach them what you know and tell them to live their lives, but they're always hostages to fortune. I've created a lot of characters that I've just left out there like a transcendent parent, and in most cases they're just free radicals with whom nobody else knows what to do. Obviously - or maybe not so obviously - if I were still around the business of juggling with a shared fantasy universe, I would have taken some of my own characters, as well as those created by others, elsewhere. If Marv wanted a Superboy character to cast into oblivion, I'm glad I put one out there to whom to do it. But I certainly would have been a different sort of custodian for that universe if I hadn't been drawn to another one.

Q: Do you think DC made a mistake in getting rid of Superboy with the "Man of Steel" reboot?

A: I think every fifteen years or so you see a major punctuation in the equilibrium to which we foolishly refer as "comic book continuity." This latest one - that we're probably already about halfway through - shows a lot more promise and wonder, I think, than did the one that immediately followed my tenure. I think it's always a mistake to cast away a still rich source of speculation and intellectual stimulation.

Q: Given how Superboy-Prime ended up at the end of "Crisis", are you surprised that Prime (and his Limbo companions) returned to active continuity? How do you feel about him being a bad guy?

A: I really haven't been following the continuity very closely. I've actually first come across books dedicated to me by name by people who are good friends, years after the fact. It could be that I'm the one living in an alternate universe.

Q: When DC decided to reboot Superman in 1986, were you given an opportunity to be part of that reboot? Did you feel a complete reboot of the character was necessary?

A: Nope, I wasn't. Whether it was necessary was a business decision rather than a creative one.

Q: To many readers, following the "Crisis on Infinite Earths", it seemed there was a conscious effort by DC to remove the writers and artists associated with the pre-Crisis Superman from the post-Crisis Superman titles. Did you feel this was the case?

A: Sometimes I do. Sometimes I think God did it.

Q: Why did you ultimately leave DC and the comic book industry?

A: My son asks me things like that all the time, and I guess the best answer is I don't really remember. I was chronically frustrated as an editor for the short time I did that, and I suppose that helped prompt me to move west and look for another way to make my fortune. Looking back at the past twenty years or so, I think the primary thing I've done since then is raise kids. Los Angeles turned out to be a surprisingly good place to do that. I once thought I moved to New Hampshire because it would be a good place to have a family, and that's where the older of my kids was born. But when I lived there I spent a whole lot of my time out of town, driving or flying or running one place or another. I'm not a provincial guy, though I do enjoy clean air. I think the kids turned out better - smarter, cannier, better able to navigate the world - than they would have been otherwise. My boy is in medical school. My little girl graduates high school this year and she's a sports phenom. I've thought lately it's getting to be time for me to be a writer again. I just haven't figured out exactly what that means yet.

Q: Recent Superman comic book continuity seems to be returning the characters to a pre-"Man of Steel" state. The Multiverse is back. Clark's a dork again. Teen Clark hung out with the Legion. Do these things give you any sense of validation of the Superman characters you grew up with and wrote about?

A: Sure. Full circle, as I said. And then the circle continues beyond the starting point again.

Q: Do you have any feelings one way or another on the legal problems on-going between Warners and the heirs of Jerry Siegel?

A: My primary feeling is interest. I wish I knew more about it; I wish anyone knew more about it. I suspect it's going to be in flux for a long time.

Q: As a Jewish American comic book writer, did you have a conscious awareness you were in a trade essentially created largely by the children of Jewish immigrants, and that you were in some ways continuing that tradition?

A: I was always aware of the Jewish circulatory system of the industry, but I didn't really become conscious of it until I lived in a place where there weren't many Jews. One of my best friends in New Hampshire was a guy with whom I'd gone to college, who was one of maybe half-a-dozen or fewer rabbis in northern New Hampshire and Vermont. I developed a Jewish identity by being away from New York, where I'd been so steeped in my ancestry that I didn't notice it was there most of the time.

Q: What prompted you to write Superman related novellas - including a beautiful story about Krypto the Super Dog - on the internet?

A: When I was writing Superman pretty much full-time, I used to joke that it was so much fun I'd do it even if they weren't paying me for it. Turns out it was true. In the case of the Krypto story, I had actually pitched it to an editor at DC as a graphic novel, which I'd still like to write, I suppose. They didn't want to hear about it at the time, and they didn't call when they did want to do it. I love dogs, and I never thought anyone who wrote Krypto stories understood either dogs or Krypto. I brought the character back to comics after many years in the late Seventies, early Eighties, trying to show how I thought he ought to be handled. Awhile afterward, a friend decided he was going to write a Krypto story and I was delighted. I told him that of course in a relatively realistic story you can't give the dog thought balloons. Anyone who's ever communicated with a dog knows they don't do it in English. He said, "Well, I'll just give him a few thought balloons, then." So I rolled my eyes and changed the subject.

Q: Do you keep up with "Superman" comic books today? If approached by DC, would you want to write Superman again or have you said all you want about the character?

A: I certainly haven't said all I want to say about the character, but I talk a lot. I don't know who would have to contact whom, and I'm not sure my doing comic book stories would be very cathartic these days. I do like graphic novels, though. That may be the way to go. I'm actually pretty interested to see what others do with the character, now that he's re-evolved into someone closer to the character I know.

Q: Finally, what did you think of 2006's "Superman Returns"? Any thoughts on TV's "Smallville"?

A: I liked Superman Returns. They did two things really deftly: (1) they dealt effectively with Superman's absence the day the Trade Center fell, much better than we ever did justifying his apparent absence during World War II, and (2) the disposition of the relationship with Lois was, I thought, just perfect and appropriately bittersweet. I hope the movie continuity progresses from that point.

I keep referring to the Smallville show as Superboy. I love it, actually. The guys putting it together really understand the mythology of it - the way Mario Puzo did before his producers tripped him up. The way you can only understand it if you're Greek or Italian or a serious geek. I've had an idea kicking around my head for a cool episode since the show began, but I haven't found a spare couple of weeks to write a spec script. I should, shouldn't I? I did that with Lois and Clark, also late, and the story editor I took it to said he loved it but it didn't fit in with that year's continuity. The previous year they would have scooped it right up, he said. Maybe. Turned out that was the last year. You know, I never thought he should marry Lois - no matter what Mort Weisinger promised a thousand years ago. I mean he "should" marry Lois in the sense of making an honest woman of her and all - but for storytelling purposes, they should never hook up successfully. Only tragically. Like Romeo and Juliet. Zeus and Leda. Batman and Talia. Know what I mean?

This interview is Copyright © 2009 by Steven Younis. It is not to be reproduced in part or as a whole without the express permission of the author.

Interviews

Introduction

The Superman Homepage has had the pleasure of interviewing various Superman Comic Book creative people about their work.

Question and Answer Interviews:

- Interview with writer Marv Wolfman about Man and Superman: The Deluxe Edition (November 2019)

- Interview with artist Claudio Castellini about Man and Superman: The Deluxe Edition (November 2019)

- Interview with artist Joe Staton about working on Superman properties over the years (November 2019)

- Interview with Christopher Priest about the Superman vs. Deathstroke story in Deathstroke #8 (November 2016)

- Interview with Sterling Gates about the 'Adventures of Supergirl' digital-first comic book series (January 2016)

- Interview with J. Michael Straczynski about “Superman: Earth One - Vol. 3” - Writer J. Michael Straczynski talks to us about the third volume in the “Superman: Earth One” graphic novel series (February 2015)

- Interview with Jim Krueger - Writer Jim Krueger talks to us about his “The Dark Lantern” story in the “Adventures of Superman” comic book title (November 2013)

- “Smallville: Season 11” Interview with Bryan Q. Miller - Writer Bryan Q. Miller talks to us about his work on the “Smallville: Season 11” comic book title (October 2012)

- “Supergirl” Interview with Mahmud Asrar - Artist Mahmud Asrar talks to us about his work on the monthly “Supergirl” comic book title (July 2012)

- “Superman/Batman” Interview with Joshua Hale Fialkov - Joshua Hale Fialkov answers our questions about “The Secret” 3-part story in “Superman/Batman” #85-87 (July 2011)

- “Supergirl” Interview with Sterling Gates - Sterling Gates answers our questions about where Supergirl is headed post “War of the Supermen” (June 2010)

- “Supergirl” Interview with Sterling Gates & Jamal Igle - Adam Dechanel chats with the “Supergirl” comic book team about the Maid of Might (March 2010)

- Behind the Scenes of the Super Friends - Four part indepth look at the “Super Friends” comic book title with artists J. Bone and Stewart McKenny (February 2010)

- Interview with Landry Q Walker and Eric Jones - The writer and artist discuss Supergirl: Cosmic Adventures in the Eighth Grade (May 2009)

- Interview with Elliot S! Maggin - Legendary Superman writer and novelist discusses his career (January 2009)

- Interview with J. Bone - Artist discusses Super Friends comic book (November 2008)

- Interview with Mark Bagley (September 2008)

- Interview with J. Torres - Writer discusses Legion of Super Heroes in the 31st Century #18 (September 2008)

- Interview with Jake Black (May 2008)

- Interview with Cary Bates (June 2008)

- Interview with Jack Briglio - Writer discusses Legion of Super Heroes in the 31st Century #14 (May 2008)

- Interview with Ken Pontac - Writer discusses Justice League Unlimited #44 (May 2008)

- Interview with Karl Kerschl (April 2008)

- Interview with J. Torres - Writer discusses Legion of Super Heroes in the 31st Century #13 (April 2008)

- Interview with J. Torres - Writer discusses Legion of Super Heroes in the 31st Century #11 (February 2008)

- Interview with Fabian Nicieza - Writer on Superman comic books (June 2007)

- Interview with Danny Fingeroth - Writer of the book Superman on the Couch (May 2007)

- Interview with Jesse McCann - Writer on the Krypto The Superdog comic books (December 2006)

- Interview with Matt Haley - Artist on the Superman Returns comic book movie adaptation (November 2006)

- Interview with Ethan Van Sciver - Artist on Superman/Batman (September 2006)

- Interview with Mark Verheiden on taking over the writing duties on Superman/Batman (April 2006)

- Interview with Matt Idelson on taking over as Superman group editor (March 2006)

- Interview with Jeph Loeb on Sam and “Superman/Batman #26” (February 2006)

- Interview with Roger Stern (December 2005)

- Interview with Marv Wolfman (November 2005)

- Interview with Gail Simone (May 2005)

- Interview with Greg Rucka (April 2005)

- Interview with Brad Meltzer [Identity Crisis] (January 2005)

- Interview with Glenn Whitmore (November 2004)

- Interview with Jeph Loeb (September 2004)

- Interview with Karl Kerschl (September 2004)

- Interview with Ron Garney (September 2004)

- Interview with Greg Rucka and Matthew Clark (May 2004)

- Interview with Ed McGuinness (March 2004)

- Interview with Brad Meltzer [Identity Crisis] (March 2004)

- Interview with Mark Millar [Superman: Red Son] (March 2003)

- Interview with Min S. Ku (September 2001)

- Interview with Jeph Loeb (May 2001)

- Interview with Joe Casey (April 2001)

- Interview with Mike S. Miller (September 2000)

- Interview with Denis Rodier (August 2000)

- Interview with Grant Morrison (December 1999)

- Interview with Mark Millar [Part 2] (November 1999)

- Interview with Mark Millar [Part 1] (April 1999)

Interviews/Articles:

- “Superman vs. Terminator” - A Chat with Fight Promoter Alan Grant. (January 2000)

- Superman: The Dailies (1939-1940) Graphic Novel Review.

- The Rebirth of Superman (Part 1) - Superman is reborn... again.

- The Rebirth of Superman (Part 2) - Eddie Barganza on taking the character in a new direction.

- The Rebirth of Superman (Part 3) - Jeph Loeb discusses writing the Man of Steel.

- Lex Luthor For President - Forget Superman. An updated Luthor's new enemies are Gore and Bush.

- Superman: Last Son of Earth - Steve Gerbern Interview - The writer discusses flip-flopping the Man of Steel's origin. (August 2000)

Krypton Club Interviews:

When “Lois & Clark” started production in 1993, there was an obvious relationship between the comic book people and the Hollywood people.

When “Lois & Clark” started production in 1993, there was an obvious relationship between the comic book people and the Hollywood people.

A trade paperback “Lois and Clark: The New Adventures of Superman”, was published, with Dean Cain and Teri Hatcher on the cover. It included reprints of comic book stories that were the inspiration for “Lois & Clark”, helping to define the characters. Comic's included are: The Story of the Century (Man of Steel miniseries #2), Tears for Titano (Superman Annual #1), Metropolis - 900 mi (in SUP #9), The Name Game (SUP #11), Lois Lane (in ACT #600), Headhunter (AOS #445), Homeless for the Holidays (AOS #462), The Limits of Power (AOS #466), and Survival (ACT #665).

A number of comic book writers and artists had roles as extras in the episode “I'm Looking Through You” (Season one, episode 4). Their presence was immortilized in the Sky Trading Card #34.

Craig Byrne, president of the online “Lois & Clark” fanclub The Krypton Club, carried out a series of interviews with comic book writers. The interviews are reprinted with permission of the Krypton Club.

- Interview with Roger Stern (June 1995)

- Interview with John Byrne (June 1995)

- Interview with Mike Carlin (July 1995)