Superman Comic Books

Superman - The New Deal Symbol of the American Way

By Tesa Pribitkin

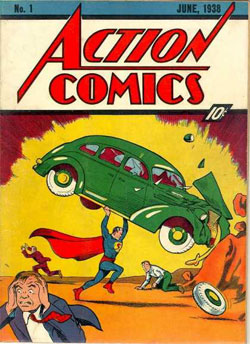

Although they generally feature the battle of good versus evil, superhero comics also reflect the beliefs of their creators and allow readers to vicariously solve the problems facing them in the real world. During the Great Depression, people searched for a hero and unexpectedly found one dressed in red and blue tights, on the cover of Action Comics #1 - Superman. Superman lived in an imaginary world but faced real life situations. Jules Feiffer, a well-known cartoonist, referred to Superman's world as a "fantasy with a cynically realistic base." (Wright 13) Superman comics provided readers with another perspective on issues such as corruption and social injustice, which affected their daily lives. Additionally, Superman demonstrated his creators' belief that such injustices should and could be overcome. The Superman phenomenon reflected the challenges facing Americans in the 1930s while celebrating the nobility of the common man.

Although they generally feature the battle of good versus evil, superhero comics also reflect the beliefs of their creators and allow readers to vicariously solve the problems facing them in the real world. During the Great Depression, people searched for a hero and unexpectedly found one dressed in red and blue tights, on the cover of Action Comics #1 - Superman. Superman lived in an imaginary world but faced real life situations. Jules Feiffer, a well-known cartoonist, referred to Superman's world as a "fantasy with a cynically realistic base." (Wright 13) Superman comics provided readers with another perspective on issues such as corruption and social injustice, which affected their daily lives. Additionally, Superman demonstrated his creators' belief that such injustices should and could be overcome. The Superman phenomenon reflected the challenges facing Americans in the 1930s while celebrating the nobility of the common man.

Superman's story reflects the lives of his creators, Jerome (Jerry) Siegel and Joseph (Joe) Shuster, who grew up as childhood friends in Cleveland, Ohio. Both were children of Jewish immigrants whose families had embraced the American way of life. Cleveland was, at that time, America's fifth largest city and had a very strong tradition of liberal Democratic politics (Trubek). Superman became a symbol for Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster's strong belief in America and Franklin Delano Roosevelt's (FDR's) New Deal. Superman comics also reflected Jerry and Joe's social struggles and fantasies. Both teenagers were short, wore glasses, and neither got a date easily. Not surprisingly, they modeled Superman's alter ego, Clark Kent, on their own shortcomings: "He would be meek and mild, like Joe and I are, and wear glasses, like we do," recalled Siegel. (Nobleman 18) Superman was also born from Jerry and Joe's love of pulp science fiction magazines featuring such heroes as Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers. But these heroes were real humans living in extraordinary worlds. Superman was to be an extraordinary person living in the real world. Perhaps Jerry was also motivated to create Superman by the death of his own father, who suffered a heart attack immediately after a robbery at the family's clothing store. Although Superman was born in a feverish twenty-four hours of creation in 1933, the boys would spend five long years before they could sell the story to a publisher. (Brancatelli 735-737)

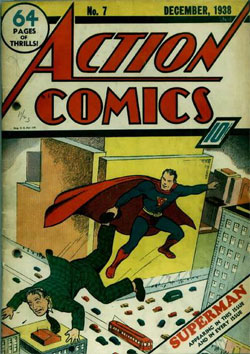

Copies of Action Comics #1 flew off of the newsstands into hundreds of thousands of kid's hands. Action Comics #1 was an immediate success, selling about 250,000 copies, but at first no one was sure exactly why. Superman did not appear on the cover of Action Comics two through six, but kids knew he was inside and started clamoring for more of his adventures. Action Comics #7, with Superman on the cover, sold over half-a-million copies. (Wright 9) Superman was quick to earn his own comic book, Superman, a daily comic strip in the newspapers, and his own radio show. Previously, the highest selling comics had sold an average of about 200,000-400,000 copies per issue, but each bi-monthly issue of Superman sold about 1,300,000 copies. (Wright 13) This underestimates the actual number of Superman readers, because comics in the 1930s and 40s were not hoarded as collector's items, but were passed around from kid to kid and avidly traded. Comic books were this young generation's version of modern television. By 1947, 95% of boys six to eleven years old, and 91% of girls that age were buying and reading comic books regularly. Between ages eighteen and thirty, 41% of men and 28% of women were steady comic book readers, a significant amount for the age. (Duncan and Smith 15)

Unlike the Pulp magazines and previous comic strips, Superman's world was realistic. Superman was the perfect Boy Scout, helping out all those in need, no matter how trivial or overwhelming the danger. (Rizzo) People could relate to Superman - kids imagined that they could fight the same bad guys presented in comics, and adults dreamt of dealing with the tough social issues in their lives the same way as Superman did. In "real life" Superman was portrayed as simply a bespectacled journalist who was always on the lookout for injustice. (Nobleman 18) From improving social living conditions to preventing corruption in high office, Superman was always able to solve the problems that everyday people could not. (Stephens) The readers began to hope that the world of Superman would become reality. Some looked at their local leaders and juxtaposed them with Superman. Others began to compare FDR and his New Deal programs with Superman's fight for social justice. Most importantly, folks began to feel empowered and began to see how little acts of justice could collectively impact their lives.

In his very first appearance in 1938, Superman dealt with social issues prevalent in the 1930s. Superman's motto from Action Comics #1 stated that he was "the champion of the oppressed. The physical marvel that had sworn to devote his existence to helping those in need!" (Siegel and Shuster 1:4) In this premier issue Superman saved a wrongly accused woman from death row, stopped a wife beating, and prevented a crook from corrupting a senator. Interestingly, Superman didn't swoop in and physically rescue the woman from death row. Instead, he confronted the governor and convinced him to pardon her. (Siegel and Shuster 1:4-7) Superman was working within the government system to promote change. Similarly, he went after the forces corrupting the senator and not the senator himself. Superman demonstrated that the American way of government would work efficiently if people were honest and cared about each other. This theme of a beneficent big government continued through all of the early Superman chronicles and reflected Siegel and Shuster's faith in FDR's New Deal.

Superman's battles against corruption and injustice were often only made possible by his alter ego, Clark Kent. For example, in Action Comics #3, Clark received a tip on a miner trapped in a cave-in. "Let me handle this assignment," he cried and soon Superman appeared and rescued the miner. (Siegel and Shuster 1: 32-35) More importantly, Superman brought the unsafe mining conditions to the attention of the oblivious mine owners by making them undergo the hardships that the miners went through daily. By viewing the situation from a worker's perspective, the mine owners were quick to make the mines a safer place to work. (Siegel and Shuster 1: 42-45) Much like the reporter Upton Sinclair in The Jungle, Clark Kent uncovered corruption, which Superman would further address. Clark Kent also helped average citizens, like failing business owners. In Action Comics #7, Clark interviewed a man losing his circus, "Poor brave old man! Faced with bitter disappointment and certain defeat, he yet has the courage to keep an optimistic front! A guy like that deserves a break... and, by golly, that's just what I'm going to give him." (Siegel and Shuster 1: 86) Here, Superman acted like President Roosevelt - both saw how badly business owners needed their help, and they both stepped up to help them. Superman executed his plan directly, approaching the circus owner and performing in his circus, attracting new paying customers. President Roosevelt set up organizations such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which helped the unemployed find jobs. (Davidson and Stoff 778) Despite his great powers and high society background, President Roosevelt always displayed a common touch. Similarly, in Action Comics #4, Superman prevented a corrupt football coach from hiring thugs as extra players. (Siegel and Shuster 1: 46-58) No person, big or small, was insignificant to Superman - in his opinion, everyone deserved an equal amount of respect and assistance.

Superman's battles against corruption and injustice were often only made possible by his alter ego, Clark Kent. For example, in Action Comics #3, Clark received a tip on a miner trapped in a cave-in. "Let me handle this assignment," he cried and soon Superman appeared and rescued the miner. (Siegel and Shuster 1: 32-35) More importantly, Superman brought the unsafe mining conditions to the attention of the oblivious mine owners by making them undergo the hardships that the miners went through daily. By viewing the situation from a worker's perspective, the mine owners were quick to make the mines a safer place to work. (Siegel and Shuster 1: 42-45) Much like the reporter Upton Sinclair in The Jungle, Clark Kent uncovered corruption, which Superman would further address. Clark Kent also helped average citizens, like failing business owners. In Action Comics #7, Clark interviewed a man losing his circus, "Poor brave old man! Faced with bitter disappointment and certain defeat, he yet has the courage to keep an optimistic front! A guy like that deserves a break... and, by golly, that's just what I'm going to give him." (Siegel and Shuster 1: 86) Here, Superman acted like President Roosevelt - both saw how badly business owners needed their help, and they both stepped up to help them. Superman executed his plan directly, approaching the circus owner and performing in his circus, attracting new paying customers. President Roosevelt set up organizations such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which helped the unemployed find jobs. (Davidson and Stoff 778) Despite his great powers and high society background, President Roosevelt always displayed a common touch. Similarly, in Action Comics #4, Superman prevented a corrupt football coach from hiring thugs as extra players. (Siegel and Shuster 1: 46-58) No person, big or small, was insignificant to Superman - in his opinion, everyone deserved an equal amount of respect and assistance.

Superman's early adventures all revolved around social inequalities and the importance of self-reliance. In Superman #3, Superman discovered a child labor workplace posing as an orphanage. Again, Superman didn't simply shut down the orphanage, but went beyond what was necessary. Upon discovering a runaway from the orphanage, Superman taught the young boy courage and urged him to help others in need. "But think of all the other children back there at the orphanage! Surely, you're not going to let them down just because you're afraid?" (Siegel and Shuster 2: 151) Once Superman convinced the young boy of the importance of standing up for what's right, Superman saved all the kids in the "orphanage" and handed over the owner to the police. (Siegel and Shuster 2: 150-170) In Action Comics #8, Superman dealt with the daily problem of bad living conditions. So many people in the Great Depression were deprived of homes and were forced to live on the streets or in slums. (Davidson and Stoff 772-774) Disgusted by these living conditions, Superman tore down the slums to make room for a new government housing project. (Siegel and Shuster 1: 98-110) For poor kids reading his adventures, Superman provided the hope of better times. In Action Comics #15, Superman helped the in-debt owner of Kidtown, where "underprivileged boys have a chance to rehabilitate themselves." He used a million dollars he earned by uncovering a stock market swindle in the previous issue to rescue Kidtown. (Siegel and Shuster 2:18-30) Superman didn't keep money for himself or his alter ego Clark Kent. Instead, he demonstrated how any person could use their talents and resources to help the less fortunate.

Superman also epitomized the life of an immigrant who came to the United States for a new life while leaving behind the old. "Just before the doomed planet, Krypton, exploded to fragments, a scientist placed his infant son within an experimental rocket-ship, launching it toward earth!" (Siegel and Shuster 1: 195) Adopted at an early age and given the name Clark Kent, it was made clear that Clark was no ordinary human. His parents lectured him on when to use his super-strength from an early age, something Superman never forgot. "This great strength of yours - you've got to hide it from people or they'll be scared of you!" "But when the proper time comes, you must use it to assist humanity." (Siegel and Shuster 1: 195-196) As an adult, Clark Kent went through life trying to fit in while hiding his origins, just as many immigrants did. Consequently, Clark competed against, and was insulted by, his colleagues, including his beloved Lois Lane, who frequently referred to him as a "spineless, unbearable coward!" (Siegel and Shuster 1: 10). Siegel and Shuster also experienced many of society's prejudices against immigrants, but still, paradoxically chased the American dream. They created Superman's alter ego, Clark Kent as a way to express their own heroic fantasies. Readers loved sharing in this secret dual identity and began to believe in their own dreams of success despite their bland and arduous lives.

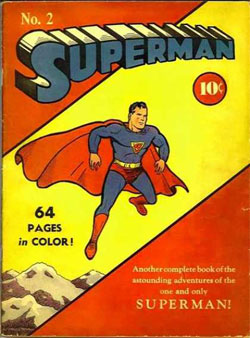

Even as nations overseas began arming themselves for a great conflict, the Superman comics promoted the American peace movement of the 1920s and 30s. The Neutrality Acts of the 1930s were examples of the United States trying to avoid combat with foreign countries. (Davidson and Stoff 805-806) Superman similarly advocated for peace in the world, but took a more active role. In Action Comics #2, Superman encountered corrupt munitions dealers. Instead of physically punishing them, he made them experience the hardships of war first hand. He then approached the opposing generals and exhorted them to "fight it out between yourselves." The generals refused, and quickly realized that they did not know why their armies were battling. (Siegel and Shuster 1: 18-30) Superman, like many Americans, believed that war was pointless and he helped the generals realize that the only persons profiting from the war were the munitions dealers. In Superman #2, Superman encountered a professor, who invented a deadly gas to be used "only in the case of a defensive war." However, three crooks attempted to use the gas formula in "Boravia, a small country exhausting its life in blood in senseless civil war...!" Siegel and Shuster were directly commenting on the civil war in Spain, which was reaching its bloody conclusion in 1939. (Trueman) Superman prevented the crooks from using the gas and destroyed the munitions works to prevent the deaths of more innocent women and children. Finally, Superman forced the two sides in the civil war to sign a peace treaty and he also destroyed the death formula. (Siegel and Shuster 2: 63-85) Interestingly, when the United States finally entered World War II, Superman stayed home fighting corruption, because his alter ego Clark Kent "failed" an eye test (Actually, he accidentally read the chart in the next room with his X-ray vision). (White 26-27) Siegel and Shuster, therefore, stayed true to the spirit of pacifism even as other comic book characters were slugging it out with Hitler and Hirohito. To Superman, the internal problems of the United States were just as important as the war overseas.

Even as nations overseas began arming themselves for a great conflict, the Superman comics promoted the American peace movement of the 1920s and 30s. The Neutrality Acts of the 1930s were examples of the United States trying to avoid combat with foreign countries. (Davidson and Stoff 805-806) Superman similarly advocated for peace in the world, but took a more active role. In Action Comics #2, Superman encountered corrupt munitions dealers. Instead of physically punishing them, he made them experience the hardships of war first hand. He then approached the opposing generals and exhorted them to "fight it out between yourselves." The generals refused, and quickly realized that they did not know why their armies were battling. (Siegel and Shuster 1: 18-30) Superman, like many Americans, believed that war was pointless and he helped the generals realize that the only persons profiting from the war were the munitions dealers. In Superman #2, Superman encountered a professor, who invented a deadly gas to be used "only in the case of a defensive war." However, three crooks attempted to use the gas formula in "Boravia, a small country exhausting its life in blood in senseless civil war...!" Siegel and Shuster were directly commenting on the civil war in Spain, which was reaching its bloody conclusion in 1939. (Trueman) Superman prevented the crooks from using the gas and destroyed the munitions works to prevent the deaths of more innocent women and children. Finally, Superman forced the two sides in the civil war to sign a peace treaty and he also destroyed the death formula. (Siegel and Shuster 2: 63-85) Interestingly, when the United States finally entered World War II, Superman stayed home fighting corruption, because his alter ego Clark Kent "failed" an eye test (Actually, he accidentally read the chart in the next room with his X-ray vision). (White 26-27) Siegel and Shuster, therefore, stayed true to the spirit of pacifism even as other comic book characters were slugging it out with Hitler and Hirohito. To Superman, the internal problems of the United States were just as important as the war overseas.

Born from the restless imagination of two teenage sons of Jewish immigrants, Superman grew to exemplify the American Dream. The Great Depression created a huge separation between the rich and poor, and the policies of the New Deal attempted to close that gap. Similarly, Superman comics reflected the hard times of the Depression and the aspirations of the New Deal. Despite his origins on a faraway planet, Superman fought his battles in the real world, where he helped Americans to see that injustice could be conquered. Meanwhile, his alter ego Clark Kent, a mild-mannered reporter for a great metropolitan newspaper, fought a never-ending battle for truth and justice. A champion for universal peace, Superman also came to support the American belief in fair play, always letting others see their wrongdoings instead of hastily punishing them. By conquering the challenges facing Americans in the 1930s and celebrating the goodness of the common man, Superman came to symbolize the American Way.

Bibliography

Brancatelli, Joe. "Superman (U.S.)." The World Encyclopedia of Comics. Ed. Maurice Horn. Vol. 6. Philadelphia: House, 1999.

Davidson, James West, and Michael B. Stoff. "Providing Jobs." America History of Our Nation. Upper Saddle Riddle: Pearson, 2009. 778.

Duncan, Randy, and Matthew J. Smith, eds. The Power of Comics. New York, London: Continuum, 2009.

Nobleman, Marc Tyler. Boys of Steel the Creators of Superman. Illus. Ross MacDonald. New York: Knopf, 2008.

Rizzo, Johnnna. "Zap! Pow! Bam! When Dire Times Called for New Heroes." National Endowment for the Humanities July-Aug. 2006: 28-29. SIRS Issues Researcher. Web. 9 Feb. 2012.

Siegel, Jerome, and Joe Shuster.

- "The Blakely Mine Disaster." Action Comics Aug. 1938: Reprinted in Superman Chronicles. Vol. 1. New York: DC Comics, 2006. 31-44.

- "Origin of Superman." Superman July 1939: Reprinted in The Superman Chronicles. Vol. 1. New York: DC Comics, 2006. 195-196.

- "Revolution in San Monte Pt. 2." Action Comics July 1938: Reprinted in Superman Chronicles. Vol. One. New York: DC Comics, 2006. 17-30.

- "Superman." Comic strip. Action Comics No. 1 June 1938: 1-13.

- "Superman and the Runaway." Superman Winter 1939: Reprinted in The Superman Chronicles. Vol. 2. New York: DC Comics, 2007. 148-170.

- "Superman, Champion of the Oppressed." Action Comics June 1938 Reprinted in Superman Chronicles. Vol. 1. New York: DC Comics, 2006. 3-16. Print.

- "Superman Champions Universal Peace!" Superman Fall 1939: Reprinted in The Superman Chronicles. Vol. 2. New York: DC Comics, 2007. 62-85.

- "Superman in the Slums." Action Comics Jan. 1939: Reprinted in Superman Chronicles. Vol. 1. New York: DC Comics, 2006. 97-110. Print.

- "Superman Joins the Circus." Action Comics Dec. 1938: Reprinted in. in Superman Chronicles. Vol. 1. New York: DC Comics, 2006. 83-96. Print.

- "Superman on High Seas." Action Comics Aug. 1939: Reprinted in The Superman Chronicles. Vol. 2. New York: DC Comics, 2007. 18-30.

- "Superman Plays Football." Action Comics Sept. 1938: Reprinted in Superman Chronicles. Vol. 1. New York: DC Comics, 2006. 45-58

Trubek, Anne. "Cleveland, the True Birthplace of Superman." Smithsonian.com. 19 Aug. 2010. accessed 23 Feb. 2012.

Trueman, Chris. "The Causes of the Spanish Civil War." History Learning Site. 2012. accessed 8 Mar. 2012.

White, Ted. "The Spawn of M.C. Gaines." All in Color for a Dime. Ed. Don Thompson and Dick Lupoff. New York: Division of Charter Communications, 1970. 17-39.

Wright, Bradford W, ed. Comic Book Nation the Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Baltimore, London: Johns Hopkins UP, 2001.